library(dplyr)

library(readr)Introduction to tidyverse

Packages introduced in this session

Before we begin, let’s introduce some crucial parts of the tidyverse ecosystem, which we will be using extensively during exercises in this chapter (and throughout the remaining chapters).

dplyr is a centerpiece of the entire R data science universe, providing important functions for data manipulation, data summarization, and filtering of tabular data. Many data-frame operations that were annoying or cumbersome to do during the R bootcamp session are easy and natural to do with dplyr.

readr provides useful functions for reading (and writing) tabular data. Think of it as a set of better alternatives to base R functions such as

read.table(). (Another very useful package is readxl which is useful for working with Excel data).

Every single script you will be writing in this session will therefore begin with these three lines of code, which load functions from these two packages.

Our example data set

Let’s also introduce a second star in this session, our example data set. The command below will read a metadata table with information about individuals published in a recent aDNA paper on the history or the Holocene in West Eurasia, dubbed “MesoNeo” (reference). Feel free to take a couple of minutes to skim the paper to get an idea about the sort of data we will be using during our exercises.

We will read the metadata of individual sequenced as part of this paper using the read_tsv() function (from the above-mentioned readr package), and store the metadata table in a variable df (it’s a short name and we’ll be typing it a lot in this session).

Yes, this function is quite magical – it can read stuff from a file stored on the internet. If you’re curious about the file itself, just paste the URL address in your browser. Even though R gives us superpowers in analyzing data, it’s never a bad thing to rely on more mundane ways to look at the information we’re dealing with.

df <- read_tsv("https://tinyurl.com/simgen-metadata")Exercise 0: Creating a new script

Now, begin by creating a new R script in RStudio, (File -> New file -> R Script) and save it somewhere on your computer as tidy-basics.R (File -> Save). Put the library() calls and the read_tsv() command above in this script.

Unlike the previous R Bootcamp session in which it didn’t really matter if you wrote in a script or R console, in this session, whenever you’re done experimenting in the R console, always record your solution in your R script. I recommend separating code for different exercises with comments, perhaps something like this:

########################################

# Exercise 1 solutions

########################################Now let’s get started!

A selection of data-frame inspection functions

Whenever you get a new source of data, like a table from a collaborator, or a data sheet downloaded from supplementary materials of a paper (our situation in this session!), you need to familiarize yourself with it before you do anything else.

Here is a list of functions that you will be using constantly when doing data science to answer the following basic questions about your data.

“How many observations (rows) and variables (columns) does my data have?” –

nrow(),ncol()“What variable names (columns) am I going to be working with?” –

colnames()“What data types (numbers, strings, logicals, etc.) does it contain?” –

str(), or better,glimpse()“How can I take a quick look at a subset of the data (first/last couple of rows)?” –

head(),tail()“For a specific variable column, what is the distribution of values I can expect in that column?” –

table()for “categorical types” (types which take only a couple of discrete values),summary()for “numeric types”,min(),max(),which.min(),which.max(). Remember that you can get values of a givencolin a data framedfby using the named-list syntax ofdf$col!

Note: Feel free to use this list as another cheatsheet of sorts! Also, don’t forget to use the ?function command in the R console to look up the documentation to see the possibilities for options and additional features, or even just to refresh your memory. Every time I look up the ? help for a function I’ve been using for decade, I always learn new tricks.

Before we move on, note that when you type df into your R console, you will see a slightly different format of the output than when we worked with plain R data frames in the previous chapter. This format of data frame data is called a “tibble” and represents tidyverse’s more user friendly and modern take on data frames. For almost all practical purposes, from now on, we’ll be talking about tibbles as data frames (they behave the same anyway).

Exercise 1: Exploring new data

Try to answer the following questions using the functions from the list above (you should decide which function is appropriate for which question).

Before you use one of these functions for the first time, take a moment to skim through its help using the ?FUNCTIONNAME command, just to build that habit of not forgetting that the help pages are always there.

What variables (i.e., columns) do we have in our data? Think about what could they mean (some will be obvious, some less so, as is always the case with unknown data from a supplementary material of a paper). What do the first couple of rows of the data look like (i.e., what form does the data take)?

How many individuals do we have metadata for?

What data types (numbers, strings, logicals, etc.) are our variables of?

Hint: Look at the list of questions and suitable functions above!

What are the columns we have that describe the ages (maybe look at those which have “age” in their name you detected with the columns() function earlier)? How many missing values (NA) are in the ageAverage column? What information does the groupAge column probably contain?

Hint: Remember that for a column vector df$COLUMN_NAME, the command is.na(df$COLUMN_NAME) gives you the value TRUE for each NA element in that column variable, and sum(is.na(df$COLUMN_NAME)) then counts the number of those NA values (because TRUE counts as 1, FALSE as 0). Alternatively, mean(is.na(df$COLUMN_NAME)) counts the proportion of these NA values (because it computes the proportion of 1s).

How many “ancient” individuals do we have in our data? How many “modern” (i.e., present-day humans) individuals (column groupAge)?

Hint: Maybe the table() function is most useful here?

Who are the mysterious “Archaic” individuals? What are their names (sampleId column) and which publications they come frome (dataSource column)? Use your data-frame row- and column-indexing knowledge from the R bootcamp session here.

Hint: We need to filter our table down to rows which have groupAge == "Archaic". This is an indexing operation which you learned about in the R bootcamp session! Remember that data frames can be indexed into along two dimensions: rows and columns. You want to filter by the rows here using a logical vector obtained by df$groupAge == "Archaic".

Do we have geographical information in our metadata? Maybe countries or geographical coordinates (or even both)? Which countries do we have individuals from?

Hint: Again, the function table() ran on an appropriate column will help here.

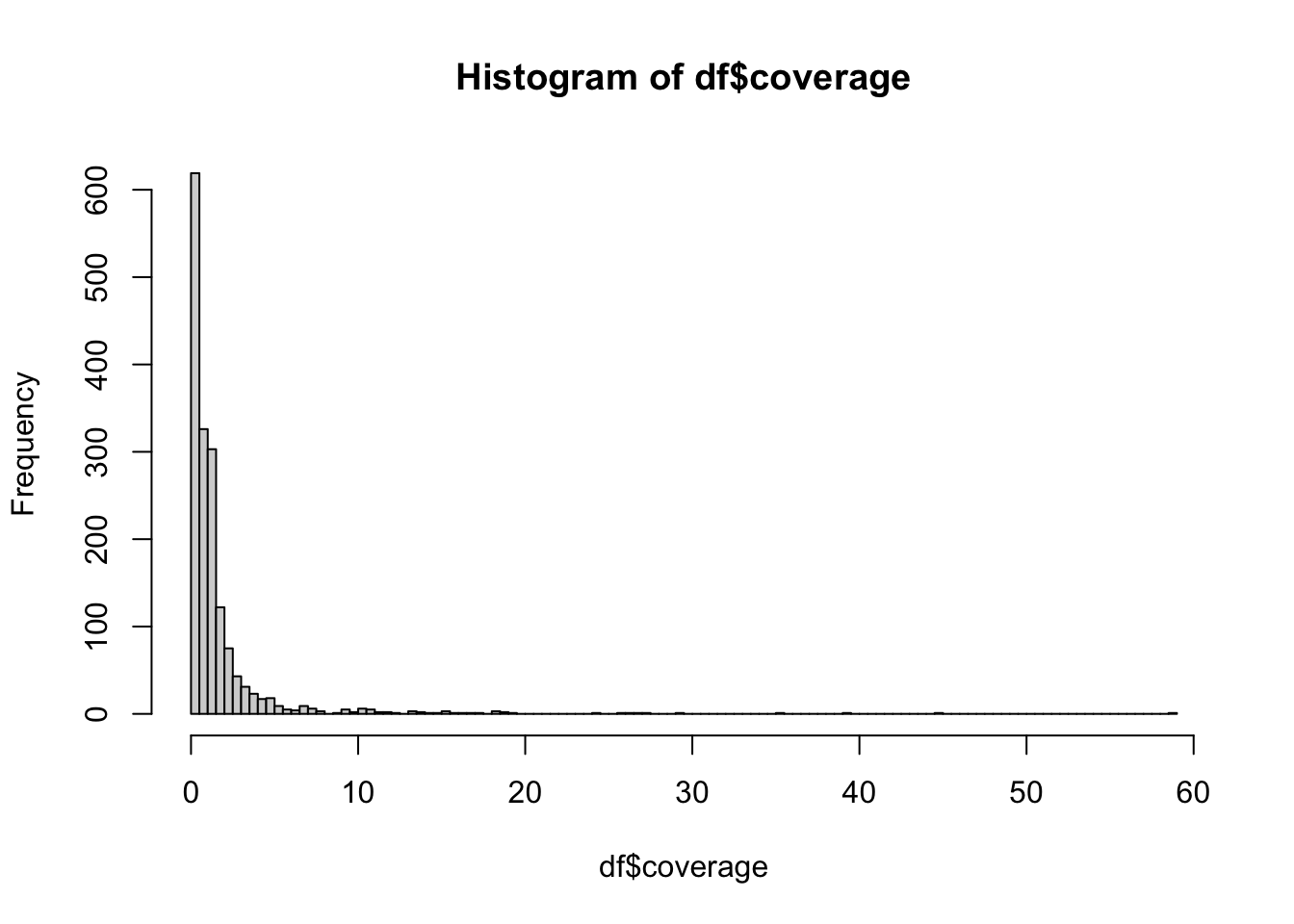

What’s the distribution of coverage of the samples (coverage column)? Compute the summary() function on the coverage column. Finally, use the hist() function to visualize this information to get a rough idea about the data.

Exercise 2: Selecting columns

We have now some basic familiarity with the format of our data and which kinds of variables/columns we have for every individual. We also got a little bit more practice on using base R for basic data-frame operations, mostly indexing (or subsetting). It’s time to learn about techniques for manipulating, modifying, and filtering this data using tidyverse, specifically the dplyr package.

Often times we end up in a situation in which we don’t want to have a large data frame with a huge number of columns. Not as much for the reasons of the data taking up too much memory, but for convenience. You can see that our df metadata table has 24 columns, which don’t fit on the screen if we just print it out (note the “13 more variables” in the output). Just try this yourself again in your R console and observe what kind of (cluttered) output you get:

df# A tibble: 4,072 × 24

sampleId popId site country region continent groupLabel groupAge flag

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 NA18486 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

2 NA18488 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

3 NA18489 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

4 NA18498 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

5 NA18499 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

6 NA18501 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

7 NA18502 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

8 NA18504 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

9 NA18505 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

10 NA18507 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

# ℹ 4,062 more rows

# ℹ 15 more variables: latitude <dbl>, longitude <dbl>, dataSource <chr>,

# age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>, ageLow <dbl>, ageAverage <dbl>,

# datingSource <chr>, coverage <dbl>, sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>,

# ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>, hgYMinor <chr>You can select which columns to pick from a (potentially very large data frame) with the function select(), the simplest and most basic dplyr function. It has the following general format:

select(<data frame>, <column 1>, <column 2>, ...)As a reminder, this is how we would select columns using a normal base R subsetting/indexing operation:

smaller_df <- df[, c("sampleId", "region", "coverage", "ageAverage")]

smaller_df# A tibble: 4,072 × 4

sampleId region coverage ageAverage

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 NA18486 WestAfrica NA NA

2 NA18488 WestAfrica NA NA

3 NA18489 WestAfrica NA NA

4 NA18498 WestAfrica NA NA

5 NA18499 WestAfrica NA NA

6 NA18501 WestAfrica NA NA

7 NA18502 WestAfrica NA NA

8 NA18504 WestAfrica NA NA

9 NA18505 WestAfrica NA NA

10 NA18507 WestAfrica NA NA

# ℹ 4,062 more rowsThis is the tidyverse approach using select():

smaller_df <- select(df, sampleId, region, coverage, ageAverage)

smaller_df# A tibble: 4,072 × 4

sampleId region coverage ageAverage

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 NA18486 WestAfrica NA NA

2 NA18488 WestAfrica NA NA

3 NA18489 WestAfrica NA NA

4 NA18498 WestAfrica NA NA

5 NA18499 WestAfrica NA NA

6 NA18501 WestAfrica NA NA

7 NA18502 WestAfrica NA NA

8 NA18504 WestAfrica NA NA

9 NA18505 WestAfrica NA NA

10 NA18507 WestAfrica NA NA

# ℹ 4,062 more rowsNote: The most important thing for you to notice here is the absence of “double quotes”. It might not look like much, but saving yourself from having to type double quotes for every data-frame operation (like with base R) is incredibly convenient.

Practice select() by creating three new data frame objects and assigning them into the following two new variables:

- Data frame

df_ageswhich contains all variables related to sample ages you found above - Data frame

df_geowhich contains all variables related to geography you found above

Additionally, the first column of these data frames should always be sampleId, so make sure this column is included in the selection.

Check visually by typing out those two data frames into your console, or using the ncol() on them, that you indeed have a smaller number of columns in these two new data frames.

Note: select() allows us to see the contents of columns of interest much easier. For instance, in a situation in which we want to analyse the geographical location of samples, we don’t want to see columns unrelated to that (like haplogrous, sex of an individual, etc. which are all part of the huge original table) and select() is the solution to this.

If your table has many columns of interest you might want to select (and save to a new variable like you did above), typing them all by hand like you did just now can become tiresome real quick. Here are a few helper functions which can be very useful in that situation, and which you can use inside the select() function as an alternative to manually typing out column names:

starts_with("age")– matches columns starting with the string “age”ends_with("age")– matches columns ending with the string “age”contains("age")– matches columns containing the string “age”

You can use them in place of normal column names. If we would modify our select() “template” above, we could do this, for instance:

select(df, starts_with("text1"), ends_with("text2"))Check out the ?help belonging to those functions (note that they have ignore.case = TRUE set by default!). Then create the df_ages table again, but this time use the three helper functions listed above.

Exercise 3: Filtering rows

In the session on base R, we learned how to filter rows using the indexing operation along the row-based dimension of (two-dimensional) data frames. For instance, in order to find out which individuals in the df metadata are archaics, we can first created a TRUE / FALSE vector of the rows corresponding to those individuals like this:

# get a vector of the indices belonging to archaic individuals

which_archaic <- df$groupAge == "Archaic"

# take a peek at the result to make sure we got TRUE / FALSE vector

tail(which_archaic, 10) [1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUEAnd then we would use it to index into the data frame (in its first dimension, before the , comma):

archaic_df <- df[which_archaic, ]

archaic_df# A tibble: 3 × 24

sampleId popId site country region continent groupLabel groupAge flag

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 Vindija33.19 Vind… Vind… Croatia Centr… Europe Neanderta… Archaic 0

2 AltaiNeandertal Alta… Deni… Russia North… Asia Neanderta… Archaic 0

3 Denisova Deni… Deni… Russia North… Asia Denisova_… Archaic 0

# ℹ 15 more variables: latitude <dbl>, longitude <dbl>, dataSource <chr>,

# age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>, ageLow <dbl>, ageAverage <dbl>,

# datingSource <chr>, coverage <dbl>, sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>,

# ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>, hgYMinor <chr>However, what if we need to filter on multiple conditions? For instance, what if we want to find all archaic individuals older than 50000 years?

One option would be to create multiple TRUE / FALSE vectors, each corresponding to one of those conditions, and then join them into a single logical vector by combining & and | logical operators like you did in the R bootcamp chapter. For example, we could do this:

# who is archaic in our data?

which_archaic <- df$groupAge == "Archaic"

# who is older than 50000 years?

which_old <- df$ageAverage > 50000

# who is BOTH? note the AND logical operator!

which_combined <- which_archaic & which_oldThen we can use that logical vector for row-based indexing (in this case, subsetting of rows) again:

df[which_combined, c("sampleId", "ageAverage")]# A tibble: 2 × 2

sampleId ageAverage

<chr> <dbl>

1 AltaiNeandertal 125000

2 Denisova 80000But this gets tiring very quickly, requires unnecessary amount of typing, and is very error prone. Imagine having to do this for many more conditions! The filter() function from tidyverse again fixes all of these problems.

We can rephrase the example situation with the archaics to use the new function filter() like this (please try it yourself!):

filter(df, groupAge == "Archaic" & ageAverage > 50000)I hope that, even if you never really programmed much before, you appreciate that this single command involves very little typing and is immediately readable, almost like this English sentence:

“Filter data frame

dffor individuals in which columngroupAgeis”Archaic” and who are older than 50000 years”.

Over time you will see that all of tidyverse packages follow these ergonomic principles.

Note: It’s worth pointing out again that — just like this is the case across the entire tidyverse — we refer to columns of our data frame df (like the columns groupAge or ageAverage right above) as if they were normal variables! Just like we did in select() above. In any tidyverse function we don’t write "groupAge", but simply groupAge! When you start, you’ll probably make this kind of mistake quite often. So this is a reminder to keep an eye for this.

Practice filtering with the filter() function by finding out which individual(s) in your df metadata table are from a country with the value "CzechRepublic".

Which one of these “Czech” individuals have coverage higher than 1? Which individuals have coverage higher than 10?

Exercise 4: The pipe %>%

The pipe operator, %>%, is the rockstar of the tidyverse R ecosystem, and the primary reason what makes tidy data workflow so efficient and easy to read.

First, what is “the pipe”? Whenever you see code like this:

something%>%f()

you can read it as:

“take something and put it as the first argument of f()`”.

Why would you want to do this? Imagine some complex data processing operation like this:

h(f(g(i(j(input_data)))))This means take input_data, compute j(input_data), then compute i() on that, so i(j(input_data)), then compute g(i(j(input_data))), etc. Of course this is an extreme example but is surprisingly not that far off from what we often have to do in data science.

One way to make this easier to read would be perhaps this:

tmp1 <- j(input_data)

tmp2 <- i(tmp1)

tmp3 <- g(tmp2)

tmp4 <- f(tmp3)

result <- f(tmp4)But that’s too much typing when we want to get insights into our data as quickly as possible with as little work as possible.

The pipe approach of tidyverse would make the same thing easier to write and read like this:

input_data %>% j %>% i %>% g %>% f %>% hThis kind of “data transformation chain” is so frequent that RStudio even provides a built-in shortcut for it:

CMD + Shift + Mon macOSCTRL + Shift + Mon Windows and Linux

Whenever you will pipe something like this in your solutions, always get in the habit of using these shortcuts. Eventually this will allow you to write code as quickly as you can think, trust me! (And take a peek at the cheatsheet) of RStudio shortcuts to refresh your memory on the other useful shortcuts! For instance, Alt + - or Option + - inserts the <- assignment operator!

Use your newly acquired select() and filter() skills, powered by the %>% piping operator, and perform the following transformation on the df metadata table, “chaining” the filter-ing and select-ion operations on the indicated columns:

- First

filter()thedfmetadata to get only those rows / individuals who are:

- “Ancient” individuals (column

groupAge) - older than 10000 years (column

ageAverage) - from Italy (column

country) - with

coveragecolumn higher than 3

- Then pipe the result of step 1. to

select()columns:sampleId,site,sex, andhgMTandhgYMajor(mt and Y haplogroups).

As a practice, try to be as silly as you can and write the entire command with as many uses of filter() and select() function calls in sequence as you can.

Hint: Don’t write the entire pipeline at once! For filter(), start with one condition, evaluate it, then add another one, etc., inspecting the intermediate results as you’re seeing them in the R console after every evaluation from your script (CTRL / CMD + Enter). Alternatively, first build up everything in the console one step at a time, then paste the result into your script to save the command on disk. This is the tidyverse way of doing data science!

Hint: What I mean by this is that the following two commands produce the exact same result:

new_df1 <- filter(df, col1 == "MatchString" & col2 > 10000 & col3 == TRUE) %>%

select(colX, colY, starts_with("ColNamePrefix"))like doing this instead:

new_df1 <- df %>%

filter(col1 == "MatchString") %>%

filter(col2 > 10000) %>%

filter(col3 == TRUE) %>%

select(colX, colY, starts_with("ColNamePrefix"))(Just take a moment to read both of these versions and compare them to convince youself they do the same.)

This works because “the thing on the left” (which is always a data frame) is placed by the %>% pipe operator as “the first argument of a function on the right” (which again expects always a data frame)!

Hopefully you now see what this idea of “build a more complex %>% pipeline one step a time” can mean in practice. Now apply these ideas to solve the filter() and select() exercise above.

Note: It is always a good practice to split long chains of %>% piping commands into multiple lines, and indenting them neatly one after the other. Readability matters to avoid bugs in your code!

Exercise 5: More complex conditions

Recall our exercises about logical conditional expressions (&, |, !, etc.).

Whenever you need to do a more complex operation, such as saying that a variable columnX should have a value "ABC" or "ZXC", you can already guess that you can do this by writing filter(df, columnX == "ABC" | column == "ZXC").

Similarly, you can condition on numerical variables, just as we did in the exercises on TRUE / FALSE expressions. For instance, if you want to condition on a column varX being varX < 1 or varX > 10, you could write filter(df, varX < 1 | var X > 10).

Practice combining multiple filtering conditions into a tidyverse %>% “piping chain” by filtering our metadata table to find individuals for which the following conditions hold:

- They are “Ancient” (

groupAgecolumn) - They are from “France” or “Canary Islands” (

countrycolumn) - Their coverage less than 0.1 or more than 3 (

coveragecolumn)

Hint: The easiest solution is to write three filter() function calls, one for each condition above:

Now select individuals who are from Germany and have coverage higher than 3 or individuals who are from Estonia with coverage less or equal to 1. Save your result to df_subset variable and print everything in this table by executing print(df_subset, n = Inf).

Supplementary question: Why do we need to print() the result like this? What happens when you just type df_subset into your R console (or execute this from your script using CTRL / CMD + Enter on its own?)

How is “chaining” several filter() command one after another different from using a single filter() command with multiple conditional expressions joined by &? How about the difference from joining them with |?

Exercise 6: Dropping columns

This one will be easy. If you want to drop a column from a table, just prefix its name with a minus sign (-) in a select() function.

Note: Yes, this also works with starts_with() and its friends above, just put - in front of them!

To demonstrate the dropping of columns in practice, here’s our df table again (just one row for brevity). Observe the columns of the resulting table:

df %>% head(1)# A tibble: 1 × 24

sampleId popId site country region continent groupLabel groupAge flag

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 NA18486 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

# ℹ 15 more variables: latitude <dbl>, longitude <dbl>, dataSource <chr>,

# age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>, ageLow <dbl>, ageAverage <dbl>,

# datingSource <chr>, coverage <dbl>, sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>,

# ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>, hgYMinor <chr>Observe what happens when we do this (and compare to the above):

df %>% select(-sampleId) %>% head(1)# A tibble: 1 × 23

popId site country region continent groupLabel groupAge flag latitude

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0 NA

# ℹ 14 more variables: longitude <dbl>, dataSource <chr>, age14C <dbl>,

# ageHigh <dbl>, ageLow <dbl>, ageAverage <dbl>, datingSource <chr>,

# coverage <dbl>, sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>, ageRaw <chr>,

# hgYMajor <chr>, hgYMinor <chr>And this:

df %>% select(-sampleId, -site) %>% head(1)# A tibble: 1 × 22

popId country region continent groupLabel groupAge flag latitude longitude

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 YRI Nigeria WestAfri… Africa YRI Modern 0 NA NA

# ℹ 13 more variables: dataSource <chr>, age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>,

# ageLow <dbl>, ageAverage <dbl>, datingSource <chr>, coverage <dbl>,

# sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>, ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>,

# hgYMinor <chr>And this:

df %>% select(-sampleId, -site, -popId) %>% head(1)# A tibble: 1 × 21

country region continent groupLabel groupAge flag latitude longitude

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0 NA NA

# ℹ 13 more variables: dataSource <chr>, age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>,

# ageLow <dbl>, ageAverage <dbl>, datingSource <chr>, coverage <dbl>,

# sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>, ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>,

# hgYMinor <chr>The columns prefixed with - are dropped from the resulting table!

Rather than typing out a long list of columns to drop, we can also do this to specify the range of consecutive columns (notice the minus - sign):

df %>% select(-(sampleId:popId)) %>% head(1)# A tibble: 1 × 22

site country region continent groupLabel groupAge flag latitude longitude

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 <NA> Nigeria WestAfri… Africa YRI Modern 0 NA NA

# ℹ 13 more variables: dataSource <chr>, age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>,

# ageLow <dbl>, ageAverage <dbl>, datingSource <chr>, coverage <dbl>,

# sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>, ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>,

# hgYMinor <chr>Alternatively, we can also use our well-known c() function, which is very useful whenever we want to drop a non-consecutive set of columns (again notice the minus - sign):

df %>% select(-c(sampleId, site, popId)) %>% head(1)# A tibble: 1 × 21

country region continent groupLabel groupAge flag latitude longitude

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0 NA NA

# ℹ 13 more variables: dataSource <chr>, age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>,

# ageLow <dbl>, ageAverage <dbl>, datingSource <chr>, coverage <dbl>,

# sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>, ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>,

# hgYMinor <chr>Note: The same “range syntax” of using : and and listing columns with c() applies also to selecting which columns to choose, not just for dropping them.

Use the : range in select() to drop every column after country (i.e., all the way to the last column in your table, whichever column this is). Do not save the result back to the df variable though! Just run the select() command on its own.

Hint: There’s another useful helper function called last_col().

Exercise 7: Renaming columns

Very often you read data frames in which columns have names which are either very long, containing characters which are not allowed, or generally inconvenient. Imagine a situation, in which you refer to a particular column very often in your workflow, but it takes too much effort to type it out, or it uses awkward characters.

After discussing select() and filter(), let’s introduce another member of the tidyverse—the function rename().

The template for using it is again very easy (again, you would replace the text in <pointy brackets> with appropriate symbols):

rename(<data frame>, <new name> = <old name>)Create a new data frame df_subset by doing the following:

- First

select()the columnssampleId,popId,country,continent,groupAge,ageAverage, andcoverage. - Pipe the result of the

select()operation using%>%into: rename()function to give some columns a shorter name:sampleId -> sample,popId -> population,groupAge -> set,ageAverage -> age. Leave thecountryandcoveragecolumns as they are (i.e., don’t rename those).

A shortcut which can be quite useful sometimes is that select() also accepts the new_name = old_name renaming pattern used by the rename() function, which allows you to both select columns (and rename some of them) all at once. To practice this, create the df_subset data frame again, but this time using just select().

When would you use one or the other (select() vs rename())`?

Exercise 8: Reorganizing columns

Let’s look at another useful application of the select() function and that is reordering columns. Our df metadata table has 24 columns. When we print it out, we only see a couple of them:

head(df, 3)# A tibble: 3 × 24

sampleId popId site country region continent groupLabel groupAge flag

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 NA18486 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

2 NA18488 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

3 NA18489 YRI <NA> Nigeria WestAfrica Africa YRI Modern 0

# ℹ 15 more variables: latitude <dbl>, longitude <dbl>, dataSource <chr>,

# age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>, ageLow <dbl>, ageAverage <dbl>,

# datingSource <chr>, coverage <dbl>, sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>,

# ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>, hgYMinor <chr>Oftentimes when doing data analysis, we often work interactively in the console, focusing on a specific subset of columns, and need to immediately see the values of our columns of interest, rather than having them buried in the rest of the (non-visible) output — how can we do this?

We already know that we can use select() to pick those columns of interest, but this removes the non-selected columns from the data frame we get. Whenever we want to retain them, we can add the call to everything(), like this:

select(<data frame>, <column 1>, <column 2>, ..., everything())Which effectively moves <column 1>, <column 2>, … to the “front” of our table, and adds everything else at the end.

Select the subset of columns you selected in the previous exercise on renaming in exactly the same way, but this time add a call to everything() at the end to keep the entire data set intact (with just columns rearranged).

Please make sure to save the result to df again, so that the metadata table has renamed columns from now on (it will be important later). Just assign the select() result back into df using the <- assignment operator.

Experiment with the function relocate() (it uses the same format as select()). Try it with our df table and with giving it a names of a couple of columns, similarly to what you did with select() above. What result do you get?

What happens when you do the same with select() (just use select() instead of relocate()) and add everything() after the last column?

Is the select() & everything() combination needed when we have relocate()?

Exercise 9: Sorting rows based on column values

When you need to sort the rows of a data frame based on a value of one or multiple columns, you will need to use the function arrange(). Again, in the spirit of the consistency across the tidyverse ecosystem, it follows exactly the same format of first giving the function a data frame to operate on, followed by a list of columns to sort by.

arrange(<data frame>, <column 1>, <column 2>, ...)Note: When you want to reverse the order of the sort, you can surround the column name in a helper function desc() (standing for “descending”).

arrange(<data frame>, desc(<column 1>), desc(<column 2>), ...)Who is the oldest individual in your data who is not an archaic individual?

Hint: Remember that you can filter() out rows corresponding to archaic individuals with the condition set != "Archaic" and then pipe %>% the result into arrange() for sorting based on the column age.

Similarly, who is the youngest ancient individual in your data in terms of its dating?

Does the same approach work for sorting text? What do you get when you try sorting based on the country column?

What do you get when you try sorting based on country and then coverage? What happens when you sort based on coverage and then country? Why is there a difference?

Does it matter what order you use filter() (on some column) and arrange() (on another column) if you’re using both functions? If yes, why? If not, why not? Think about the amount of work these functions have to do in either of those two scenarios.

Exercise 10: Mutating tables

Mutating a table means adding a column for a new variable. Again, as with the previously introduced functions select(), filter(), and rename() and arrange(), it follows a consistent tidyverse pattern:

df %>% mutate(<new column name> = <vector of the required length>)Not surprisingly, the new column is assigned a vector of the same length as the number of rows in a data frame. What we often do is this:

df %>% mutate(<new column name> = <expression involving other columns>)because mutate() allows us to refer to other columns in the data frame already present.

Please note that you can also modify an existing column using the same command. In this case, <new column name> above could simply be the name of an already existing column.

To demonstrate this on a couple of exercises, let’s actually remove some columns from our data frame first. They were originally created by mutate() in the first place and this gives as a useful opportunity for practice (because we’ll soon add them back again ourselves):

df <- select(df, -set)The important aspect of mutate is that it is a vectorized operation. We can’t create a column and give values to only some rows. Here are several ways how we could do this, starting with a simple example of assignment of sex description based on sex chromosomes:

1. if_else()

if_else() accepts a logical vector (i.e., a vector of TRUE / FALSE values), and produces another vector which contains one value for each TRUE, and another value for each FALSE. Here is an example:

v <- c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE)

if_else(v, 123, -123)[1] 123 123 -123 123 -123Notice that we get 123 for each TRUE and -123 for each FALSE.

The above can be a bit confusing, so spend a bit of time playing around with if_else(). For instance, create a different logical vector variable (containing an arbitrary TRUE or FALSE values, up to you), and have the function produce values “hello” and “bye” depending on TRUE / FALSE state of each element of the logical vector variable.

Just get familiar with this vectorized thinking because whenever we do data science, it almost always happens in this vectorized fashion (such as operating on every single value in a column of a table at once, like we’ll do soon).

As mentioned, this function is extremely useful whenever we need to generate values of a new column based on values of another column(s). The general pattern for using it inside a mutate() call is this:

df %>%

mutate(<new_column> = if_else(<logical vector>, value_for_true, value_for_false))You can see that the column df$sex contains chromosome sex determination of each individual as either XY or XX. Use the if_else() function in a mutate() call to create a new column sex_desc which will contain a character vector of either “male” (if sex == "XY") or else assigns “female”.

Hint: Again, you might want to build an intuition first. Create a small vector of a mix of “XY” and “XX” values and store it in a variable sex. Then experiment with if_else()-based assignment of “female” and “male”. When you’re sure you got it, apply it to the data frame in the mutate() call to solve this exercise.

Run table(df$sex, df$sex_desc) to make sure the assignment of sex description worked as expected. How do you interpret the results? Did we miss something? If we did, what is wrong?

It turns out there is an individual with a Klinefelter syndrome. A male carrying an extra X chromosome. Clearly the logic of our if_else() is incorrect because this individual was incorrectly assigned as “female”. Take a look at your mutate() and if_else() code again to make sure you see why we did it wrong. How would you fix the mutate() (or rather the if_else()) command to work correctly and correctly assign the XXY individual as “male”?

This is a lesson to always remember to check assumptions in your data, even the ones you consider trivial. Functions such as table() and unique() are extremely useful for this.

Note: I got this originally wrong when I was preparing these materials. So this is a real-world cautionary tale.

Let’s practice if_else() a bit more. First, use filter() to look at the values of the age column for present-day individuals in the 1000 Genomes Project data (dataSource == "1000g"). What ages do you see?

The 1000 GP individuals are missing an age value. It should be set to 0. Let’s fix that now and correct the metadata table.

You already know that you can get a logical vector indicating whether a certain element of another vector (here, the column age) is NA or not via the function is.na(). Use is.na(age) in the if_else() to set the age column with the mutate() function so that:

- Rows where

is.na(age)isTRUEwill be set to 0, and - Rows where

is.na(age)isFALSEwill be set toage(because those values don’t need to be replaced).

Note: Using mutate() to replace values of an existing column (rather than creating a new column) is done very often in data science, particularly in “clean up” operations like this one. Your data will never be “perfect” (especially if you get it from some other source) and you will need to do a lot of so-called “table munging” to prepare it for analysis and plotting, just like we’re doing here.

Hint: Again, if you need help, you can start slowly by creating a toy example variable age which will have a vector of a mix of numbers, including some NA values. Then practice creating an if_else() expression which will return 0 in place of NA values in this vector, and keep every other value intact.

2. case_when()

if_else() does only work on binary TRUE or FALSE conditions. But what if we want to create a new column with values of multiple categories, not just two. Recall our original column set (which we dropped from our df table earlier), which had values either “Archaic”, “Ancient”, or “Modern”.

For this purpose, case_when() is perfect. It works in a very similar manner to if_else(), but allows not-just-binary categorization. Consider this vector of numbers between 1 and 30:

v <- 1:20If we wanted to assign a value “less_than_10” or “10_or_more” to each element, we could use the function if_else() like this:

if_else(v < 10, "less than 10", "10 or more") [1] "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10"

[6] "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10" "10 or more"

[11] "10 or more" "10 or more" "10 or more" "10 or more" "10 or more"

[16] "10 or more" "10 or more" "10 or more" "10 or more" "10 or more" What if we want to introduce three or more categories? case_when() to the rescue! Try running this yourself on the vector v created above.

case_when(

v < 10 ~ "less than 10",

v == 10 ~ "exactly 10",

v > 10 ~ "more than 10"

) [1] "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10"

[6] "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10" "less than 10" "exactly 10"

[11] "more than 10" "more than 10" "more than 10" "more than 10" "more than 10"

[16] "more than 10" "more than 10" "more than 10" "more than 10" "more than 10"Remember how we had a slightly annoying time with doing vectorized conditional logical expressions on TRUE / FALSE vectors in our Bootcamp session? Now it’s all paying off!

Every one of the three conditions actually result in a logical vector, and case_when() decides which value to produced for each element of that vector based on whichever results in TRUE.

The case_when() function has a very useful optional argument called .default =, which determines the value it should return whenever a particular location in the logical vector either results in all FALSE (so none of the conditions would apply), or whenever it produces a NA value (so none of the conditions can apply even in principle).

First, let’s start simple and reimplement the mutate() operation to add the sex_desc column again (just to practice on something we already know) this time using case_when() and implementing the three conditions (“XX”, “XY”, “XXY”) individually. Additionally, use the .default = argument of case_when() to assign “unknown” as a value of the sex_desc column.

In the exercise on conditional expressions, you learned about & and | operators which make it possible to combine multiple conditions into a single TRUE / FALSE vector. Of course, this means that the conditions inside the case_when() function can also utilize those operators.

Create a new column sex_set which will contain the following values:

sex == "XX" & age == 0should produce"female (present-day)",(sex == "XY" | sex == "XXY") & age == 0should produce"male (present-day)",sex == "XX" & age > 0should produce"female (ancient)",(sex == "XY" | sex == "XXY") & age > 0should produce"male (ancient)",- any other combination should default to “other”

I provided the code of the logical conditions for you, you just have to put them in a case_when() call appropriately, modifying the solution to the previous exercise. Verify the outcome by doing table(df$sex_set) again.

Why did I put parenthesis around the sub-clause involving the | OR operator? What happens if we don’t do this?

Note: Again, admittedly this might seem arbitrary to you — why would we need something like this for data analysis and statistics? But this kind of “arbitrary categorization” is extremely useful to generate factor categories for plotting, especially for plotting with ggplot2 later. So keep this in mind for the time being.

Remember how we removed the set column, which originally contained values “Modern”, “Ancient”, or “Archaic”, depending on whether the individual was a present-day modern human, ancient modern human, or an archaic individual, respectively? Use what you learned in this exercise on if_else() or case_when() to reconstruct this column again based on information in the remaining columns. (There is many possible solutions, so don’t be afraid to think creatively!)

Hint: Using information in age and the names of the three archaic individuals (combined with the .default argument of case_when() is probably the easiest solution).

Note the use of .after = in my solution to the previous exercise. Look up the help of mutate() in ?mutate to see what it does and why I used it.

Exercise 11: Summarizing tables

You have already learned how to operate on rows (filter(), arrange()), columns (select(), rename()), and both rows and columns (mutate()). We have one remaining piece of the puzzle and that is operating on groups of rows. This takes the tidyverse functionality to an entire whole level and allows you to do many more powerful things with tabular data and compute summary statistics.

In this section, we will will cover the functions group_by(), summarize(), and various associated “slice functions”.

1. group_by()

Take a look at the first couple of rows of our metadata table again:

df# A tibble: 4,072 × 26

sample population country continent age coverage set site region

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 NA18486 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

2 NA18488 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

3 NA18489 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

4 NA18498 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

5 NA18499 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

6 NA18501 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

7 NA18502 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

8 NA18504 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

9 NA18505 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

10 NA18507 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

# ℹ 4,062 more rows

# ℹ 17 more variables: groupLabel <chr>, flag <chr>, latitude <dbl>,

# longitude <dbl>, dataSource <chr>, age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>,

# ageLow <dbl>, datingSource <chr>, sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>,

# ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>, hgYMinor <chr>, sex_desc <chr>, sex_set <chr>Now run the following code in your R console and carefully inspect the output (and compare it to the result of the previous command):

group_by(df, continent)# A tibble: 4,072 × 26

# Groups: continent [4]

sample population country continent age coverage set site region

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 NA18486 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

2 NA18488 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

3 NA18489 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

4 NA18498 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

5 NA18499 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

6 NA18501 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

7 NA18502 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

8 NA18504 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

9 NA18505 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

10 NA18507 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

# ℹ 4,062 more rows

# ℹ 17 more variables: groupLabel <chr>, flag <chr>, latitude <dbl>,

# longitude <dbl>, dataSource <chr>, age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>,

# ageLow <dbl>, datingSource <chr>, sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>,

# ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>, hgYMinor <chr>, sex_desc <chr>, sex_set <chr>You can probably see that the data hasn’t changed at all (same number of columns, same number of rows, all remains the same), but you can notice a new piece of information in the output:

[...]

# Groups: continent [4]

[...]The output says that the data has been grouped by the column/variable continent. This means that any subsequent operation will be applied not to individual rows, like it was with our mutate() operations earlier, but they will now work “per continent”. You can imagine this as the group_by() function adding a tiny bit of invisible annotation data which instructs downstream functions to work per group.

Before we move on to computing summary statistics, let’s also note that we can, of course, group based on multiple columns. For instance, in our data, we should probably not summarize based on continent but also on age, splitting individuals based on the broad age sets like this:

group_by(df, continent, set)# A tibble: 4,072 × 26

# Groups: continent, set [10]

sample population country continent age coverage set site region

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 NA18486 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

2 NA18488 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

3 NA18489 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

4 NA18498 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

5 NA18499 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

6 NA18501 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

7 NA18502 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

8 NA18504 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

9 NA18505 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

10 NA18507 YRI Nigeria Africa 0 NA Modern <NA> WestAfrica

# ℹ 4,062 more rows

# ℹ 17 more variables: groupLabel <chr>, flag <chr>, latitude <dbl>,

# longitude <dbl>, dataSource <chr>, age14C <dbl>, ageHigh <dbl>,

# ageLow <dbl>, datingSource <chr>, sex <chr>, hgMT <chr>, gpAvg <dbl>,

# ageRaw <chr>, hgYMajor <chr>, hgYMinor <chr>, sex_desc <chr>, sex_set <chr>Grouping is just the first step though, and doesn’t do anything on its own…

2. summarize()

Why is grouping introduced above even useful? The most simple use case is computing summary statistics on the data on a “per group” basis using the summarize() function. This function works a little bit like mutate(), because it creates new columns, but it only creates one row for each group.

For instance, we could compute the mean coverage of each individual in a group like this, and arrange the groups by the coverage available (try running this in your R console to see this in practice!):

df %>%

group_by(continent, set) %>% # first create groups

summarize(mean_coverage = mean(coverage)) %>% # then create summaries for each group

arrange(desc(mean_coverage))`summarise()` has grouped output by 'continent'. You can override using the

`.groups` argument.# A tibble: 10 × 3

# Groups: continent [4]

continent set mean_coverage

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Asia Archaic 35.3

2 Europe Archaic 24.4

3 Africa Ancient 4.99

4 America Ancient 2.67

5 Asia Ancient 1.71

6 Europe Ancient 1.41

7 Africa Modern NA

8 America Modern NA

9 Asia Modern NA

10 Europe Modern NA Notice that the result has only three columns, unlike the many columns in the original df table! We have a column for each variable we grouped over, and we have the new column with our summary statistic. Additionally, we only have 10 rows, one row for each combination of continent and set. So, this is kind of similar to mutate() (it creates new variables/columns), but different.

What does the NA value for “Modern” individuals in the output of the previous code chunk? Take a look at the original data df to answer this question.

summarize() is even more powerful than that because we can compute many different things at the same time, for each group! This next exercise is an example of that.

As you know, the mean (such as the mean_coverage we computed right above) is computed as a sum of a set of values divided by their count. Use the group_by() and summarize() code exactly like you did above, but instead of computing the mean() directly, compute it manually by doing (in a summarize() call):

sum_coverage = sum(coverage)(the sum of coverages for each group),n = n()(the number of values in each group),mean_coverage = sum_coverage / n(using the two quantities just computed to calculate the mean)

To make things a little tidier, arrange() the results by the column mean_coverage.

Once you have your results, save this new table in a variable called df_summary.

Look up the function ?ungroup. Why is it useful?

Bonus exercise (feel free to skip this): How would you compute 95% confidence interval for the mean coverage using the group_by() and summarize()? Remember that you will need standard deviation (R function sd()) and also the number of observations (function n()). Look up confidence interval equation on Wikipedia.**

slice_ functions

Finally, in addition to computing various summaries on groups using summarize(), we have five “slicing” functions at our disposal, each of which extracts specific row(s) from each defined group. These functions are:

slice_head(n = 1)takes the first row,slice_tail(n = 1)takes the last row,slice_min(<column>, n = 1)takes the row with the smallest value of, slice_max(<column>, n = 1)takes the row with the largest value of, slice_sample(<col> = 1)takes one random row.

What is the lowest coverage individual in each continent and set group? While you’re doing this, filter() out the set of “Modern” individuals because they are not meaningful anyway (they have NA coverages), composing the entire command as a series of steps in a %>% pipeline.

At the end of your %>% pipeline, pipe your results into relocate(continent, set) to make everything even tidier.

Modify your %>% pipeline for the exercise above to answer who is the oldest individual we have available on each continent?

Exercise 12: Writing (and reading) tables

Above you create a summary table df_summary. Let’s try writing it to disk using write_tsv(). The .tsv stands for “tab-separated values” (TSV) which is a file format similar to another file you might have heard about, the “comma-separated values” (CSV) file. They can be opened with Excel too, in case this is useful at some point, but they are very useful for computational workflows.

Look up the help in ?write_tsv. What are the parameters you need to specify at minimum to save the file? This function has all of the useful options saved as defaults, so there’s not much you have to do. Still, look up the options!

What are other means of writing files you found in ?write_tsv? How would you read a CSV file into R? What about other file formats?

Hint: Look up ?read_csv.

A very useful R package is readxl, for reading and writing Excel files. Google this package, and install it with install.packages("readxl"). If you want and have some Excel file on your computer, try reading it into R with library(readxl); read_excel("path/to/your/excel/file").

“Take home exercises”

Which country has the highest number of aDNA samples (i.e., samples for which set == "Ancient“). How many samples from Estonia, Lithuania, or Latvia do we have?

Hint: Use the group_by(country) and summarize() combo again, together with the n() helper function.

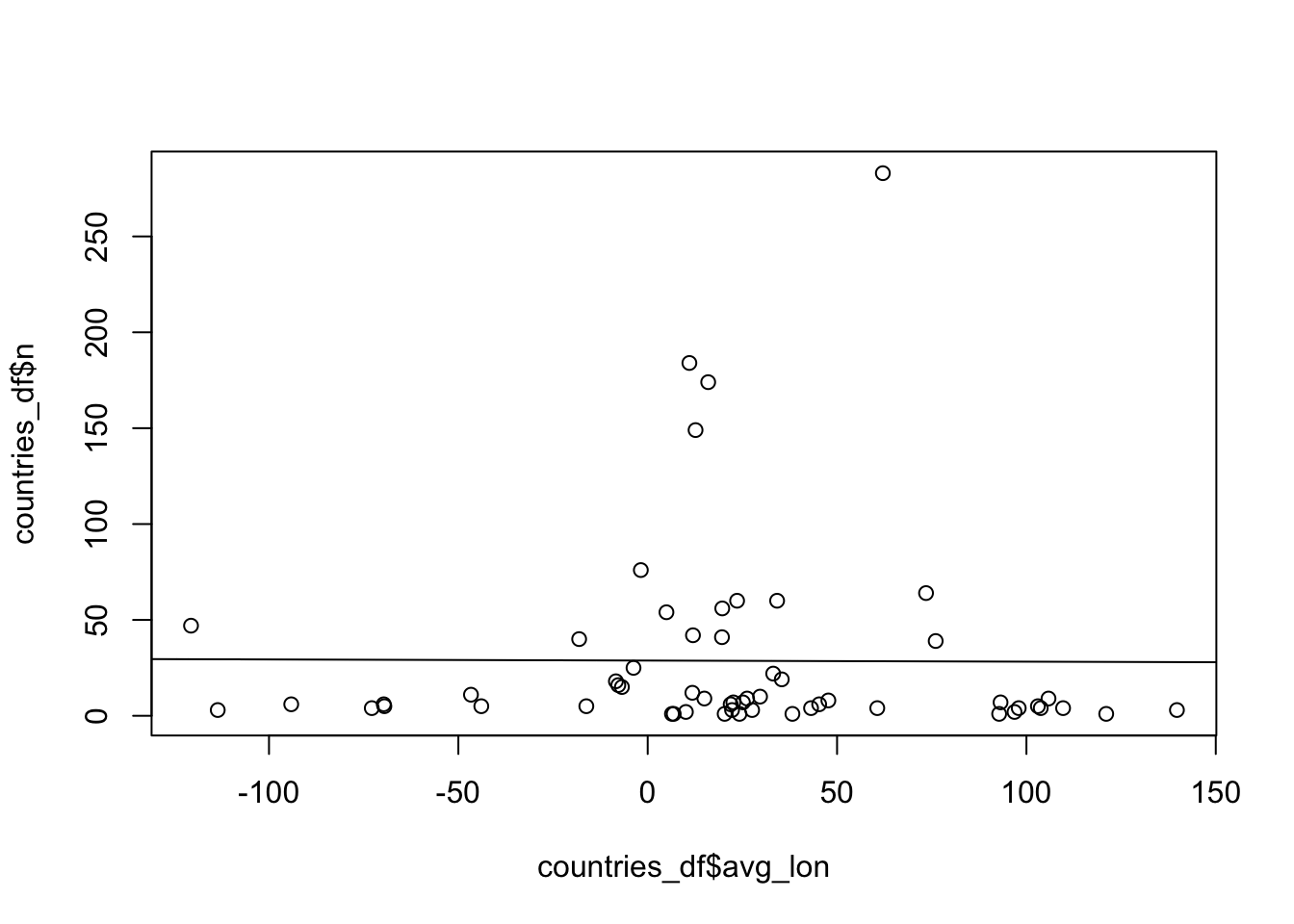

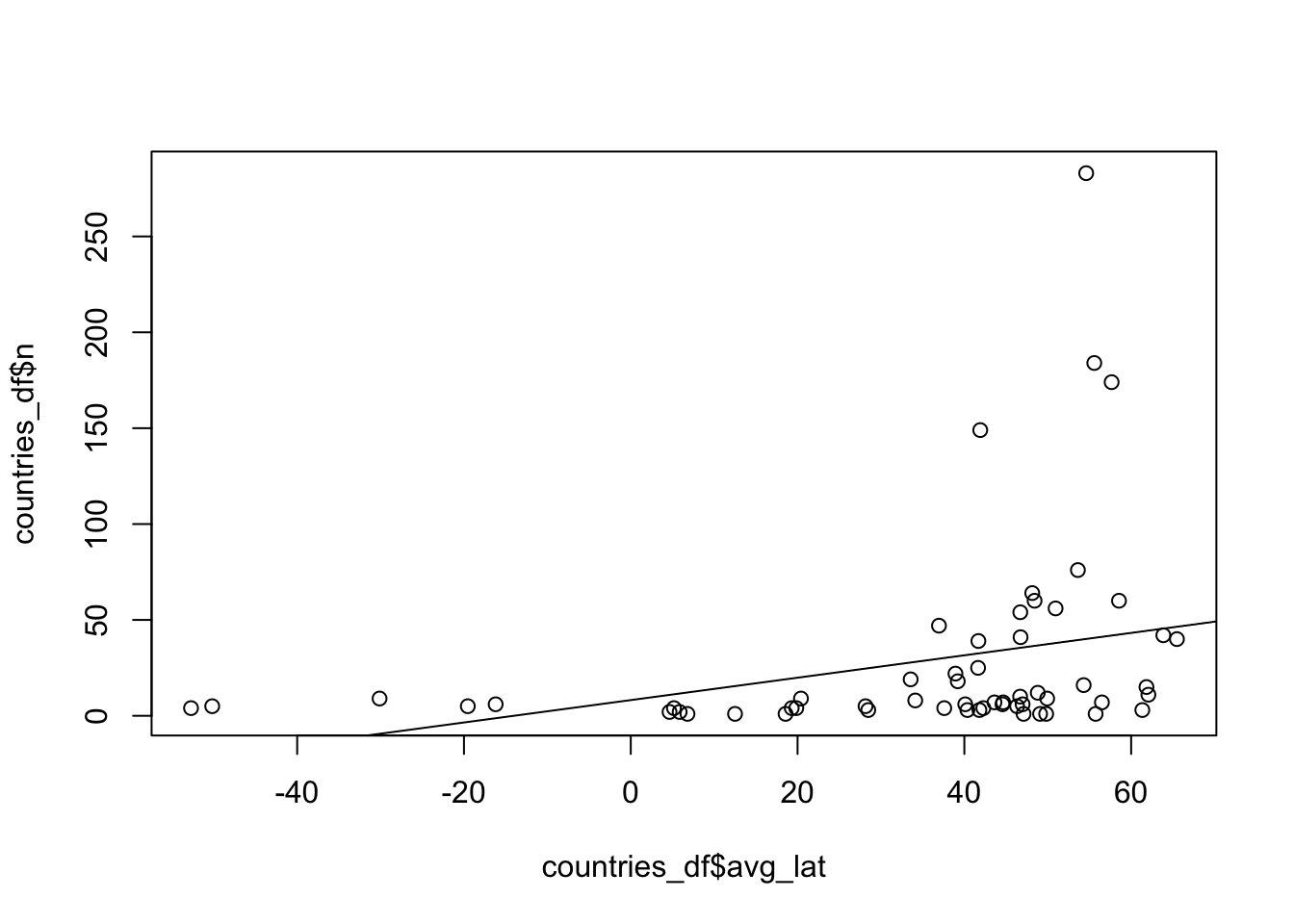

Is there any evidence (real or not — just out of curiousity!) of a potential bias in terms of how many set == "Ancient" samples do we have from a country and the geographical location of that country, such as the average longitude or latitude of samples from there? Compute a linear model using the lm function of the count the n count of samples from each country as a function of avg_lat or avg_lon (average latitude and longitude) of samples in each country (all of these quantities computed with group_by() and summarize() like you did above).

Hint: If you’re not familiar with this, look up the linear model function ?lm or perhaps this tutorial to see how you can build a linear regression between a response variable (like our count n) and an explanatory variable (such as average longitude or latitude of a country), as computed by the group_by() and summarize() combination (the result of which you should save to a new data frame variable, to be used in the lm() function).

Take your own data and play around with it using the concepts you learned above. If the data isn’t in a form that’s readily readable as a table with something like read_tsv(), please talk to me! tidyverse is huge and there are packages for munging all kinds of data. I’m happy to help you out.

Don’t worry about “getting somewhere”. Playing and experimenting (and doing silly things) is the best way to learn.

For more inspiration on other things you could do with your data, take a look at the dplyr cheatsheet.

In each following session, you’ll have the opportunity to do the same. The next session will focus on more real-world insights from data, and the section after that will focus on creating beautiful visualizations using the ggplot2 package.

Closing remarks

Hopefully you’re now learning that really integrating these couple of tidyverse “verbs” gives you an entirely new natural way of not just working and modifying and filtering data, but “thinking in data” (as pretentious and hippy this must seem to you right now).

When you watch experts doing data science using tidyverse in real time, like an experienced colleague helping you out, you will see that they can “think about the data” at the same time as they are typing tidyverse commands. Over time, with practice, you will get there too.

And this is actually just the beginning! The true power of data science arrives when we learn ggplot2 visualization later. ggplot2 uses the same philosophical principles ad the dplyr commands we practiced above, but allows you to “visualize information at the same time as you’re thinking about it”.